Scientist Explorer: How to Become a Botanist

Table of Contents

ToggleHow to Become a Botanist: Exploring Plant Science in Today’s World

Ever noticed a dandelion pushing through a sidewalk crack? That little plant is doing something pretty amazing – breaking through solid concrete just to reach the sun. When you see that, you’re watching plant science in action. As trees leaf out and flowers bloom all around us, April is a great time to talk about the people who study these plant stories – botanists.

What Is A Botanist (Botany)?

Botanists study plants – everything from tiny moss to giant redwoods. They look at how plants grow, reproduce, and get along in their environments. Think of botanists as the people who figure out the stories behind what you see in gardens, forests, and even that crack in the sidewalk.

Understanding Botanical Science:

What Botanists Do:

When you walk through a garden center and see plants labeled with their water needs or light requirements, you’re seeing botanical research at work. Botanists are the ones who figured out what each plant needs to thrive.

Some botanists focus on a single type of plant – like orchids or oak trees – while others study how all the plants in a forest work together. Their day might involve collecting leaves in a remote forest, looking at plant cells under a microscope, or running experiments to see how plants handle drought or heat.

Where They Work:

- Research universities: These botanists might be studying why some plants can handle drought while others can’t, or how plants defend themselves against insects.

- Botanical gardens: Next time you visit a botanical garden, look for botanists tending special plant collections, studying rare species, or teaching visitors about plant life.

- Government agencies: Groups like the Forest Service need botanists to keep track of native plants, spot invasive species, and help decide how to manage public lands.

- Private industry: When you take plant-based medicine or eat a crop variety that resists disease, you’re benefiting from botanists’ work in the private sector.

- Breweries and wineries: Ever wonder why your favorite beer or wine tastes the way it does? Botanists help understand the plants that create those flavors – from selecting hop varieties to improving grape growing.

Key Responsibilities:

Walk alongside a botanist for a day and you might find yourself:

- Hiking through a forest counting different plant species

- Using a microscope to look at plant cells

- Collecting seeds from wild plants for conservation

- Testing how plants respond to different growing conditions

- Teaching others about plant life

Many botanists also help restore damaged ecosystems. They figure out which native plants should go back into an area and in what order – like putting together a complex puzzle where all the pieces need to work together.

Impact:

Next time you eat a meal, thank a botanist. The vegetables on your plate likely came from crop varieties developed through botanical research. Many botanists work to create plants that can handle challenges like drought or disease while still producing good food.

That park down the street? Botanists helped plan which plants would grow well together there. The medicine in your cabinet? Many come from compounds found in plants that botanists studied.

And as weather patterns shift around the world, botanists are helping figure out how plant communities will change and which ones might need our help to survive.

Recent Discoveries in Botany

Every time botanists venture into fields, forests, or labs, they uncover something new. In the last few years alone, scientists have made discoveries that change how we see plant life—from finding that plants “talk” to each other through underground networks to learning that some plants have surprisingly complex ways of sensing their environment.

Plants Talk to Each Other

Look down at the soil under your feet in a forest. Underneath is what some scientists call the “wood wide web” – a network of fungal threads that connect trees and plants together. Through these connections, plants share nutrients and even send warning signals when insects or disease show up. It’s sort of like plants having their own underground internet!

Scientists found that when one tree is attacked by insects, it can send chemical warnings through these networks to neighboring trees, which then ramp up their own defenses before the bugs even reach them. Pretty smart for organisms without brains, right?

Plants Remember Things

You might think you need a brain to learn or remember, but plants prove otherwise. Take the Venus flytrap – it can actually count! When an insect touches the trigger hairs in its trap, the plant “counts” how many touches happen before snapping shut. This helps it know the difference between an actual meal and a random raindrop.

Some plants can even be trained, similar to how you might train a pet. Scientists found that plants exposed to the same harmless stimulus over and over will eventually stop responding to it – they learn it’s not worth the energy to react.

Plants That Handle Tough Conditions

Next time you’re in a really dry area, look at the plants growing there. Some desert plants can wait decades for rain, basically sleeping until conditions are right. When water finally arrives, they spring to life, flower, and set seed in just days or weeks.

Scientists studying these plants are finding ways to help crop plants handle drought better too. They’re looking at the genes that let desert plants conserve water so well, hoping to bring some of those traits into the plants we grow for food..

Plants as Medicine Factories

That garden herb you use in cooking might be a tiny medicine factory. Botanists have found that many plants make compounds that fight bacteria, viruses, or cancer cells. As we face more antibiotic-resistant germs, these plant compounds could be our next line of defense.

The challenge is that many plants with potential medicines grow in threatened habitats like rainforests. Botanists are racing to find and study these plants before they disappear.

Nature’s Carbon Capture

Trees and plants naturally pull carbon dioxide from the air – they’re like living air filters. But botanists have found that some plants are much better at this than others. They’re studying how certain farming practices can help plants lock more carbon in the soil, which could help with climate change.

When you see a grassy prairie or a forest, you’re looking at a natural carbon capture system that botanists are helping us understand and improve.

Plant Pollution Detectors

Some plants change color or shape when exposed to certain pollutants – they’re like living sensors. Botanists have found plants that react to everything from heavy metals in soil to air pollution.

These plant sensors are often cheaper and easier to use than electronic equipment, especially in remote areas. In some places, scientists plant specific flowers along roadsides – if the flowers change color, it’s a sign that air quality is getting worse.

Why Study Plant Science?

Imagine being the first person to figure out how trees talk to each other, or discovering a new plant compound that fights cancer. Botanists get to solve these kinds of puzzles every day, connecting the plant world to human needs.

Research Opportunities

Plant science brings together old-school field observation with cutting-edge technology. On Monday, a botanist might be hiking through a forest collecting samples; by Wednesday, they could be using DNA sequencing to unlock genetic codes.

Right now, botanists are working on some pretty cool projects:

- Watching how plants communicate through underground networks

- Finding wild plant relatives of crops that might help our food plants become more resilient

- Studying how forests recover after fires

- Looking at how plants and their pollinators keep their complicated relationships in sync even as seasons shift

- Mapping the genes that let some plants make valuable medicinesn light

If you’re interested in other sciences too, botany connects to just about everything. Love chemistry? Plant biochemistry shows how plants make thousands of useful compounds. Into technology? Botanists use everything from drones to DNA sequencers. Enjoy art? Many botanists are also skilled illustrators and photographers.

Career Applications

When you think “plant scientist,” you might picture someone in a forest with a notebook, but modern botanists work in all sorts of places:

- Farm fields: Developing crops that can handle drought or pests with fewer chemicals

- Biotech labs: Creating plants that produce medicines, biofuels, or new materials

- Conservation areas: Protecting rare plants and restoring damaged ecosystems

- City planning offices: Designing green spaces that cool urban areas and filter air pollution

- Classrooms and museums: Helping others understand plant life

Speaking of where botanists are needed right now – there are some areas that really need new scientists:

Climate-smart agriculture – As weather patterns change, we need botanists to develop food crops that can handle new conditions. This means working with farmers to test different plant varieties and growing methods.

Ecosystem restoration – When forests burn or wetlands are drained, botanists help bring them back. They know which plants should go in first, which ones can handle disturbed soil, and how to create the right conditions for a healthy plant community to develop.

Urban greening – As more people live in cities, we need botanists who know which plants can thrive between buildings, on rooftops, and along busy streets. The right plants can cool hot city neighborhoods, filter air pollution, and even grow food in small spaces.

Global Impact

Plants touch almost every part of human life, and botanists help us use them wisely:

They keep our food supply going. When disease threatens a crop – like when a fungus nearly wiped out bananas in the 1950s – botanists find resistant varieties that farmers can grow instead. They also help farmers use less water and fewer chemicals while still growing enough food.

They help protect wild places. Botanists identify areas with rare plants that need protection and help create plans to manage these special places. When they save a rare plant, they’re often saving the insects, birds, and other animals that depend on it too.

They’re part of the climate solution. Mangrove forests, peatlands, and old-growth forests are some of the best carbon-storing systems on Earth. Botanists show us how to protect and restore these places, helping address climate change through plant power.

They find materials and inspiration for new technology. The super-sticky burrs that inspired Velcro are just one example. Botanists studying how lotus leaves stay clean led to self-cleaning paints and fabrics. Plants have solved all sorts of problems through evolution, and botanists help us learn from these solutions.

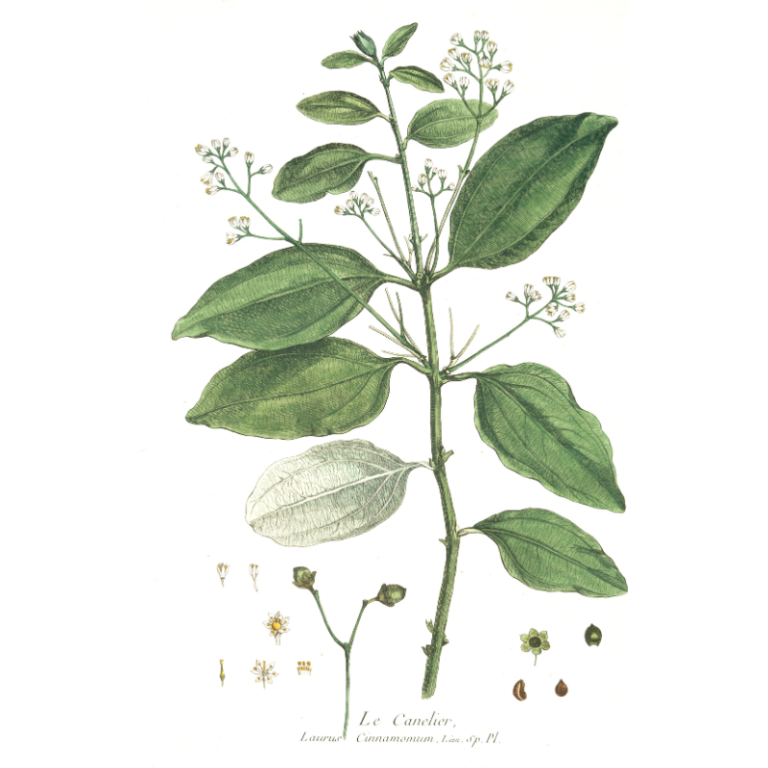

Meet a Leading Botanist: Dr. Cassandra Quave

When Dr. Cassandra Quave enters a forest, she doesn’t just see trees and flowers – she sees potential medicines waiting to be discovered. As a leading ethnobotanist, she combines traditional knowledge about plant remedies with cutting-edge science to find new ways to fight disease.

Background:

Dr. Quave holds a PhD in Biology with a focus on ethnobotany and is a tenured Associate Professor at Emory University. She serves as Curator of the Emory Herbarium and leads the Quave Research Group, which documents traditional uses of plants and studies their potential for addressing global health challenges, particularly antibiotic resistance.

Growing up with a disability (she had her right leg amputated below the knee as a child due to a congenital condition), Dr. Quave developed remarkable resilience and determination. These qualities, combined with her scientific curiosity, have driven her pioneering work connecting traditional plant knowledge with modern medical challenges.

Current Work:

Dr. Quave’s research focuses on finding plant compounds that can fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria – one of the most urgent threats to global health. Rather than looking for plants that kill bacteria directly (like conventional antibiotics), her team often searches for compounds that disrupt bacterial communication or disable their ability to cause disease.

She conducts fieldwork around the world, especially in Mediterranean regions and the Balkans, working with traditional healers to document plant remedies that have been used for generations. These plants become candidates for laboratory testing, where her team isolates and identifies active compounds that could become new treatments.

Click here to find out more about Dr. Quave and other fascinating scientists in our Scientist Spotlight Series

Key Achievements:

Dr. Quave has made several groundbreaking discoveries about plants’ medical potential:

- Identified compounds from the European chestnut that can disarm MRSA (a dangerous antibiotic-resistant bacteria) without killing it, potentially avoiding the problem of developing resistance

- Published over 100 scientific papers on medicinal plants and their compounds

- Established a massive extract library containing thousands of plant samples for testing against pathogens

- Co-founded PhytoTEK LLC, a drug discovery company focused on plant-based solutions to antibiotic resistance

- Authored “The Plant Hunter: A Scientist’s Quest for Nature’s Next Medicines,” a memoir about her research journey

- Received prestigious grants from the National Institutes of Health and Department of Defense for her innovative research

- Created the first free online Botanical Medicine course available to the public

Career Journey:

“I never set out to become an ethnobotanist,” Dr. Quave often shares. “I was pre-med with plans to become a surgeon.” A transformative undergraduate research experience in the Amazon rainforest changed her path. There, she witnessed how indigenous communities relied on local plants for medicine and realized the untapped potential of these botanical remedies.

After earning her PhD, she faced challenges securing funding for her unconventional approach to antibiotic research. “Many colleagues thought looking at traditional plant remedies was outdated,” she explains. “But I believed these plants held secrets that could help address modern medical problems.” Her persistence paid off, and her lab now leads the field in discovering plant compounds that work differently than conventional antibiotics.

Advice for Newcomers:

“Get comfortable being uncomfortable,” Dr. Quave advises aspiring botanists. “Whether you’re hiking through thorny brush to collect plants, learning a new language to interview traditional healers, or mastering complex laboratory techniques, this field demands versatility and perseverance.”

She emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary thinking: “The most exciting discoveries happen at the intersection of different fields. Don’t just learn botany – understand chemistry, ecology, anthropology, and even history. Plants connect all these domains.”

For students interested in ethnobotany specifically, she recommends: “Learn to listen. Traditional knowledge about plants comes from generations of careful observation and experimentation. Approach this knowledge with respect, and you’ll find insights that laboratory science alone might miss.”

Notable Professionals in Botanical Science

Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer

Dr. Kimmerer bridges indigenous knowledge and western science as a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and Distinguished Professor at SUNY. Her book “Braiding Sweetgrass” explores plant relationships through both scientific and traditional lenses. She founded the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment and studies how traditional harvesting practices can sometimes benefit plant communities rather than harm them.

Dr. Stefano Mancuso

Plants don’t have brains, but they can solve problems, remember things, and even communicate. Dr. Mancuso studies how plants sense and respond to their world – a field sometimes called plant neurobiology.

His work has shown that plant roots can detect and respond to at least 15 different environmental signals, from gravity to touch to chemicals in the soil. Plants might not think like we do, but Dr. Mancuso’s research reveals they have their own form of intelligence that helps them survive and thrive.

Dr. Nalini Nadkarni

Did you know there’s a whole world of plants living in the tops of trees? Dr. Nadkarni was one of the first scientists to study this “canopy” ecosystem, using mountain climbing equipment to reach the treetops in rainforests.

Beyond her groundbreaking research, Dr. Nadkarni is known for making science accessible to everyone. She’s brought science programs to prisons, helping inmates connect with nature even while incarcerated. She also worked with Mattel to create a scientist Barbie doll, showing girls that they too can explore the treetops and beyond.

Understanding the Science

Ever watched a houseplant bend toward a window? Or noticed how some trees lose their leaves in fall while others stay green all year? These everyday observations are the starting points for botanical science.

When you look at plants through a botanist’s eyes, you start seeing patterns and connections everywhere. That weed in your garden and the vegetables you’re growing might be engaged in a chemical war underground. The timing of spring flowers relates to complex environmental cues and plant hormones. Even the way a leaf is shaped tells a story about where that plant evolved.

Basic Principles:

At its heart, botany looks at a few key ideas:

- How plants work: Plants make their own food using sunlight, water, and air – a process called photosynthesis. They have specialized tissues to move water up from roots and food from leaves to growing parts.

- Plant parts and what they do: From roots that anchor and absorb water to leaves that capture sunlight, each plant part has specific jobs.

- How plants interact: Plants compete for light and nutrients, but they also help each other through connections with fungi and bacteria in the soil.

- Plant names and relationships: With over 400,000 known plant species, botanists need systems to organize all this diversity. They group plants based on their features and evolutionary relationships.

Key Methods

Botanists use all sorts of approaches to study plants:

In the field, they might count different plant species in an area, measure tree growth, or watch which insects visit specific flowers. It’s like being a nature detective, looking for clues about how plants live and interact.

In greenhouses, they can control growing conditions to see exactly how plants respond to different amounts of water, light, or nutrients. This helps answer questions like: “How little water can this plant survive on?” or “How does this plant defend itself against insect attacks?”

DNA analysis has changed plant science dramatically. By looking at plant genes, botanists can see how different species are related, track rare plants in the wild, and even find genes that help plants resist disease or drought.

Chemical analysis lets botanists identify the compounds plants make – from the pigments that color flowers to the defensive chemicals that deter insects. These plant compounds might become medicines, food additives, or industrial materials.

Equipment Used

A botanist’s toolkit might include:

- In the field: Plant presses to preserve specimens, GPS units to record locations, soil testing kits, and good old-fashioned hand lenses for looking at plant details

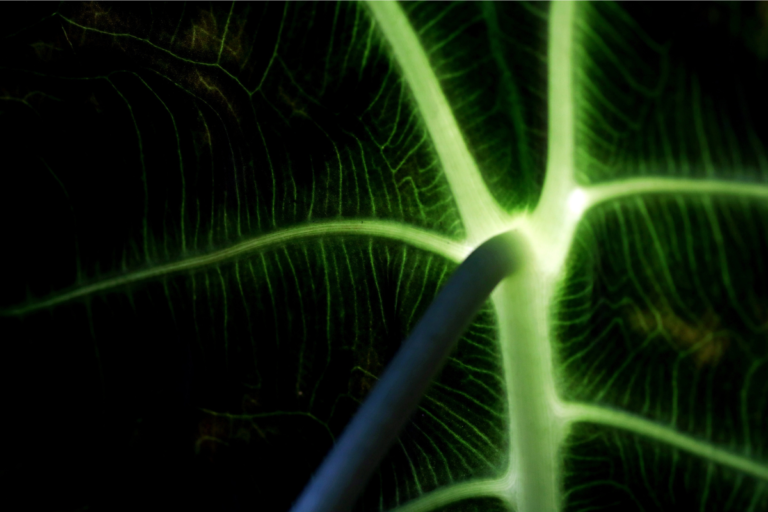

- In the lab: Microscopes ranging from simple dissecting scopes to powerful electron microscopes that can see cell structures

- For experiments: Growth chambers that control light, temperature, and humidity; sensors that measure plant responses to stimuli

- High-tech tools: DNA sequencers, drones for aerial surveys of plant communities, spectrometers that analyze plant chemistry, and 3D imaging systems

Current Challenges

Plants face big challenges today, and botanists are working to understand and address them:

Climate change is shifting where plants can grow. Some plants are moving to higher elevations or latitudes as their old habitats warm. Others can’t move fast enough and may disappear. Botanists track these changes and look for ways to help vulnerable plants adapt or migrate.

Invasive species are plants that grow outside their native range and cause problems for native plants. Think of kudzu taking over the American South or purple loosestrife filling wetlands. Botanists study how these invaders work and test methods to control them without harming native plants.

Habitat loss happens when forests are cut down, wetlands are filled in, or grasslands are plowed up. Botanists help identify which areas are most important to protect and how to restore damaged habitats.

Food security is about making sure everyone has enough nutritious food to eat. Botanists develop crop varieties that can handle drought, heat, pests, and diseases while still producing good harvests.

Education and Career Pathways

Maybe watching plants has sparked your interest in botany. How do you turn that interest into a career studying plants? There’s no single path – botanists come to the field through different routes, but most involve both classroom learning and hands-on experience with plants.

Think of learning botany like growing a garden – you’ll start with basic seeds of knowledge, add the right nutrients through education, and give yourself time to develop and branch out into specialties. The good news is that many successful botanists started just by being curious about the plants around them and following that interest wherever it led.

Some botanists knew from childhood they wanted to work with plants. Others discovered botany during college or even later in life after working in other fields. Whether you’re a student planning your education or someone looking to change careers, there’s a path into plant science that can work for you.

Academic Requirements

- Bachelor’s degree in botany, plant biology, horticulture, forestry, or related fields (like ecology or environmental science)

- Master’s degree for research positions, consulting work, and advanced roles

- PhD for university teaching, leading research programs, and top positions in botanical institutions

- Associate degrees in horticulture or forestry technology for some technical support positions

- Certificate programs in specialized areas like arboriculture or landscape management

Key Courses:

- Plant anatomy and morphology (how plants are built)

- Plant physiology (how plants function)

- Plant taxonomy and systematics (how plants are classified and related)

- Ecology and plant communities

- Genetics and molecular biology

- Chemistry and biochemistry

- Soils and nutrition

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and mapping

- Research methods and experimental design

- Statistics and data analysis

- Climate science and meteorology

- Entomology (for plant-insect interactions)

- Mycology (for plant-fungal relationships)

- Conservation biology

Useful Skills:

- Plant identification in the field and lab

- Microscopy and laboratory techniques

- Scientific writing and communication

- Data collection and management

- Statistical analysis and interpretation

- Field sampling methods

- GPS and mapping capabilities

- Photography for documentation

- Growing plants under controlled conditions

- Isolating and analyzing plant compounds

- Project management

- Working both independently and collaboratively

- Problem-solving and critical thinking

- Attention to detail and observation

- Programming (Python, R) for data analysis

- Grant writing for research funding

Certification Needs:

- Wetland delineation certification for environmental consulting

- Arborist certification for tree care

- Natural areas management certification

- Pesticide applicator license for many research and management positions

- Seed certification for those working in seed banking or production

- SCUBA certification for aquatic botanists

- Wilderness first aid for field botanists

- Professional soil scientist certification for some research positions

- Teacher certification for formal education positions

- Native plant society certifications in plant identification

Career Development

Most botanists start small and grow their careers over time, branching out like a tree as they gain experience and specialized knowledge. The path isn’t always straight – you might find unexpected opportunities that take your career in exciting new directions.

Entry Level Positions

- Field technicians collecting plant data for research projects or environmental assessments

- Laboratory assistants running experiments and maintaining plant collections

- Horticulturists caring for plants at botanical gardens or parks

- Nursery managers propagating and growing plants

- Seed collectors for conservation programs

- Research assistants at universities or government agencies

- Botanical garden educators leading tours and programs

- Agricultural extension technicians helping farmers with crop issues

- Environmental inspectors monitoring invasive species or protected plants

- Plant conservation technicians working on habitat restoration

Career Progression:

Early Career (0-5 years):

- Gaining technical skills and field experience

- Building plant identification expertise

- Learning laboratory methods

- Understanding research protocols

- Developing professional connections

Mid-Career (5-15 years):

- Leading field teams or laboratory groups

- Designing and directing research projects

- Specializing in particular plant groups or ecosystems

- Contributing to scientific publications

- Mentoring newer botanists

- Managing larger conservation or research initiatives

Senior Career (15+ years):

- Directing research programs or departments

- Serving as botanical garden director or curator

- Working as a university professor or research scientist

- Consulting on major conservation or restoration projects

- Shaping policy related to plant conservation

- Writing books or major publications

- Leading professional organizations

Specialization Options:

- Plant systematics and taxonomy (classifying and naming plants)

- Ethnobotany (how people use plants culturally)

- Paleobotany (fossil plants)

- Plant ecology (how plants interact with environment)

- Economic botany (plants used for products)

- Agronomy (crop science)

- Bryology (mosses and liverworts)

- Lichenology (lichens)

- Mycology (fungi, often studied alongside plants)

- Dendrology (trees and woody plants)

- Plant pathology (plant diseases)

- Plant genetics and breeding

- Restoration ecology

- Conservation botany

- Phytochemistry (plant chemistry)

- Ethnopharmacology (medicinal plants)

Additional Training:

Throughout your career, you’ll likely need ongoing education to keep up with advances in the field:

- Advanced plant identification workshops

- New laboratory techniques and equipment training

- GIS and spatial analysis courses

- Botanical illustration and photography

- Statistical methods and software

- Specialized propagation techniques

- Conservation genetics methodologies

- Scientific communication and writing

- Leadership and project management

- Grant writing and research funding strategies

- Policy and regulatory frameworks affecting plants

- Climate change adaptation planning

Essential Terms and Concepts

- Photosynthesis

- This is how plants make their own food using sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide from the air. Next time you take a breath, thank a plant – photosynthesis produces the oxygen we breathe while capturing carbon dioxide. It’s like plants run tiny solar power plants inside their leaves, turning sunlight into the energy they need to grow.

- Plant Communities

- Look at a meadow, forest, or desert, and you’ll see that certain plants typically grow together. These plant communities form because the plants share similar needs and tolerances. Understanding these communities helps botanists predict how areas might change over time or respond to disturbances like fire or flooding.

- Ethnobotany

- This is the study of how people use plants for food, medicine, materials, and cultural practices. Ethnobotanists work at the intersection of human culture and plant science, often learning from traditional knowledge holders. Their work has led to important medicines like aspirin (originally from willow bark) and helped preserve traditional plant knowledge that might otherwise be lost.

- Phenology

- Ever noticed how cherry trees bloom around the same time each spring, or how leaves change color in fall? Phenology looks at the timing of these natural events in plants’ lives. By tracking when plants flower, fruit, or lose their leaves, scientists can see how these cycles respond to weather patterns and climate change.

- Biodiversity

- This term describes the variety of plant species in an area. High biodiversity means many different kinds of plants are present, which usually creates a more stable and resilient ecosystem. Think of biodiversity like a diverse investment portfolio – when conditions change, having many different types of plants means some will likely thrive even if others struggle.

- Mycorrhizae

- These are partnerships between plant roots and fungi in the soil. The fungi help plants gather water and nutrients, while plants provide fungi with sugars from photosynthesis. It’s like plants having an extended root system – the fungal network can be hundreds of times larger than the plant’s roots alone. About 90% of land plants form these partnerships, making them crucial for plant survival.

- Taxonomy

- This is the science of naming and classifying plants. Each plant has a two-part scientific name (like Quercus alba for white oak) that helps botanists worldwide know exactly which plant is being discussed. Think of taxonomy as nature’s filing system – it helps us organize plants based on their evolutionary relationships rather than just how they look.

- Succession

- When bare ground gets colonized by plants over time, different species appear in a predictable sequence – that’s succession. After a forest fire, for example, fast-growing grasses and wildflowers might come first, followed by shrubs, small trees, and eventually large trees. It’s like watching a slow-motion relay race where each group of plants passes the baton to the next.

- Plant Adaptations

- These are special features that help plants survive in their environments. Desert plants might have waxy coatings to prevent water loss or deep roots to reach groundwater. Plants in shady forests often have large leaves to capture limited light. These adaptations are solutions plants have evolved over millions of years to solve environmental challenges.

- Native Plants

- These are plants that have evolved in a particular region over thousands of years, developing relationships with local insects, birds, and other wildlife. When you plant native species in your garden, you’re supporting these ecological relationships. It’s like inviting the original inhabitants back to the neighborhood, where they already know how to thrive without extra water or care.

Resources and Next Steps

Academic Programs

f you’re interested in studying botany, many universities offer relevant programs. Look for:

- Botany, plant biology, or plant science departments at major universities

- Natural resource programs with forestry or rangeland specialties

- Agricultural schools with plant breeding or crop science options

- Environmental science programs with plant ecology components

Some programs with strong plant science include the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the University of California-Berkeley, and Cornell University. Look for programs that provide field experience and research opportunities alongside classroom learning.

Not ready for a full degree program? Many botanical gardens, extension offices, and nature centers offer short courses on plant identification, gardening, or local ecology.

Professional Organizations

Joining plant-focused organizations can help you connect with others in the field:

- Botanical Society of America: Offers student memberships, grants, and networking opportunities. Their annual conference is a great place to present research and meet others in the field.

- American Society of Plant Biologists: Focuses on plant physiology and molecular biology, with resources for both researchers and educators.

- Ecological Society of America: For those interested in how plants interact with their environment and other organisms.

Hands-On Experience

Internship Opportunities:

Internships give you real-world experience working with plants:

- Botanical gardens: Places like the Chicago Botanic Garden, New York Botanical Garden, Missouri Botanical Garden, and Longwood Gardens offer internships in horticulture, conservation, education, and research.

- Federal agencies: The Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hire seasonal botanists and plant technicians for field seasons.

- Conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, and local land trusts need help with plant surveys, invasive species management, and habitat restoration.

- Research institutions: The Smithsonian, Field Museum, and similar institutions offer internships working with plant collections or assisting with research.

- Seed banks and nurseries: Organizations like the Center for Plant Conservation and Native Plant Trust have programs focused on rare plant propagation and conservation.

- Sustainable agriculture: Organic farms, university extension programs, and sustainable agriculture research centers offer experiences in applied plant science.

- Local parks and natural areas: Many city and county park systems have internship programs in natural resources management.

- Herbaria: These plant specimen libraries need help mounting, cataloging, and digitizing plant collections.

Research Experience:

Getting involved in plant research can open doors:

- Many universities have undergraduate research programs where you can work with botanists.

- Undergraduate research programs: Many universities have structured programs where you can work with botanists on ongoing research projects.

- REU (Research Experiences for Undergraduates): This NSF-funded program places students in summer research positions at field stations and universities.

- Field stations: Places like the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, Archbold Biological Station, and biological field stations in different ecosystems offer courses and research opportunities in plant ecology.

- Citizen science: Projects like Project BudBurst, invasive plant mapping programs, and rare plant monitoring let you contribute to real research while learning.

- Independent study: Develop your own research question with guidance from a professor or professional botanist.

- Laboratory volunteering: Many university labs welcome volunteers to help with plant care, sample processing, or data management.

- Herbarium work: Helping curate plant collections teaches taxonomy and plant diversity.

- Conservation monitoring: Many states have Natural Heritage Programs that involve volunteers in monitoring rare plant populations.Field stations in different ecosystems offer courses and research opportunities.

- Citizen science projects like plant monitoring programs let you contribute to real research while learning.

Industry Connections:

Building professional connections can lead to job opportunities and collaborations. Look for ways to connect with:

- Agricultural technology companies: Firms like Corteva, Bayer, and smaller plant breeding companies hire botanists to develop new crop varieties and growing methods.

- Conservation organizations: Land trusts, The Nature Conservancy, and similar groups employ botanists for habitat assessment, management planning, and restoration.

- Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies: Companies researching plant-based medicines and compounds need botanists who understand plant chemistry and diversity.

- Ecological consulting firms: These companies hire botanists to conduct plant surveys, wetland delineations, and environmental impact assessments.

- Seed and nursery industry: Commercial growers need botanists for plant propagation, breeding, and production.

- Environmental education centers: Nature centers, science museums, and botanical gardens hire botanical educators.

- Publishing and media: Science writers, botanical illustrators, and nature photographers with plant knowledge are needed for field guides, websites, and educational materials.

- Government agencies: Local, state, and federal natural resource departments employ botanists for various roles.

- Professional associations: Joining groups like the Botanical Society of America or the Society for Economic Botany connects you to job postings and networking opportunities.

Current Trends and Future Outlook

Industry Developments

The field of botany is evolving rapidly as new technologies and global challenges create both opportunities and needs for plant expertise:

- Automated plant phenotyping: New imaging technologies are revolutionizing how we measure plant traits and responses, allowing for high-throughput screening of thousands of plant varieties.

- CRISPR and gene editing: Precision tools for genetic modification are changing plant breeding from a process that took decades to one that can produce results in months.

- Vertical farming and controlled environment agriculture: Growing plants in stacked layers using LED lighting is creating new roles for botanists in urban food production.

- Plant biologics: Companies are developing plant-based pharmaceuticals and vaccines that can be produced more affordably than traditional methods.

- Endangered species banking: Advanced conservation techniques are preserving plant genetic material through seed banks, tissue culture, and cryopreservation.

- Plant-based materials: Innovations in plant-derived fibers, plastics, and construction materials are creating sustainable alternatives to petroleum products.

- Botanical data integration: Big data approaches are connecting plant information across disciplines, from genomics to ecology to climate science.

- Microbiome research: Understanding the communities of microorganisms associated with plants is opening new approaches to plant health and productivity.

Job Market Projections:

The job market for botanists is growing, with particularly strong demand in conservation, sustainable agriculture, and biotechnology. As we face challenges like climate change and feeding a growing population, plant expertise becomes increasingly valuable.

Some exciting new directions in botany include:

- Overall demand for plant scientists is expected to grow about 5-7% over the next decade

- Demand for specialists in plant genetics and breeding could see 10-15% growth

- Conservation botanists will see increased opportunities as climate change impacts accelerate

- Agricultural plant scientists will be needed as food security challenges intensify

- Botanical education positions are expanding as interest in native plants and sustainable landscaping grows

- Plant-based pharmaceutical research is creating new positions in both academic and private sectors

- Ecological restoration specialists are increasingly needed for large-scale habitat rehabilitation projects

- Urban forestry and green infrastructure positions are expanding in cities around the world

- Plant data scientists who can analyze complex botanical datasets are in high demand

- Botanists with expertise in invasive species management face steady job growth

Emerging Specialities:

These growing areas in plant science offer exciting career possibilities for new botanists:

- Agroecology: Designing farming systems based on ecological principles for greater sustainability

- Urban botany: Developing plant solutions for cities, from green roofs to food production

- Conservation genetics: Using DNA analysis to guide plant conservation efforts

- Climate adaptation specialists: Helping ecosystems and agriculture adapt to changing conditions

- Restoration ecology: Rebuilding damaged ecosystems using plant community knowledge

- Plant biosecurity: Preventing and managing invasive plant threats

- Food system botanists: Connecting plant production, distribution, and consumption in more sustainable ways

- Ethnobotanical conservation: Preserving traditional plant knowledge alongside the plants themselves

- Plant stress physiology: Understanding how plants respond to environmental stresses like drought and heat

- Botanical data science: Applying big data approaches to plant research questions

- Plant-based bioremediation: Using plants to clean up environmental pollution

- Botanical art and communication: Translating plant science for public engagement

Exploring Further

Recommended Reading:

- “Botany for Gardeners” by Brian Capon: A friendly introduction to plant science concepts with clear explanations and illustrations.

- “The Hidden Life of Trees” by Peter Wohlleben: Explores how trees communicate and support each other through underground networks.

- “Lab Girl” by Hope Jahren: A memoir about a life in botanical science that beautifully connects personal story with plant biology.

- “Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Wall Kimmerer: Weaves indigenous wisdom with scientific knowledge about plants.

- “The Triumph of Seeds” by Thor Hanson: An exploration of how seeds have shaped human history and natural systems.

- “What a Plant Knows” by Daniel Chamovitz: Reveals the surprising ways plants sense and respond to their environment.

- “Plants of the Gods” by Richard Evans Schultes: A classic ethnobotanical work on culturally significant plants.

- “A Field Guide to Your Local Flora”: Regional plant identification guides help you connect with plants in your area.

Online Resources:

- iNaturalist: An app where you can photograph plants, get help identifying them, and contribute to scientific knowledge.

- Plants of the World Online: Kew Gardens’ database with information on thousands of plant species.

- Botanical Society of America’s PlantingScience: Connects students with botanical mentors for science projects.

- Native Plant Network: Resources for propagating native plants for conservation and landscaping.

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s Native Plants Database: Information on North American native plants.

- USDA PLANTS Database: Comprehensive information on U.S. plants, including range maps and characteristics.

- Biodiversity Heritage Library: Historical botanical books and illustrations available for free.

- Your local extension service website: Practical plant information specific to your region.

- Cornell’s Botany Online Resources: Learning modules on plant biology concepts.

Professional Development:

- Workshops at botanical gardens: Many offer specialized training in plant identification or other botanical skills.

- Field courses: Organizations like the Eagle Hill Institute offer intensive week-long courses in specific botanical topics.

- Online webinars: Professional societies regularly host presentations on current research you can watch from home.

- Native plant society training: Local chapters often offer certification in native plant knowledge.

- Master Gardener programs: Available through extension services in most states, providing solid botanical training.

- Wilderness medicine courses: Important for botanists doing remote fieldwork.

- GIS and mapping workshops: Essential skills for many botanical careers.

- Herbarium curation training: Learn to collect, prepare, and maintain scientific plant specimens.

- Scientific writing workshops: Improve your ability to communicate botanical findings.

- Botanical illustration courses: Combine art and science to document plant features.

Wrap Up

Next time you see a plant – whether it’s a mighty oak tree or a tiny weed growing through a sidewalk crack – take a moment to think about the science behind it. That plant is solving problems, responding to its environment, and playing a role in the web of life around it.

Botanists help us understand these plant stories and put them to work solving human problems – from feeding people to making medicines to addressing climate change. Their work connects the green world outside our windows to our everyday lives in countless ways.

Whether you’re considering botany as a career or just want to understand the plants around you better, there’s always something new to discover in the plant world. Maybe the next plant story waiting to be told is one you’ll help uncover.

Next Steps for Aspiring Marine Biologists:

- Start observing: Begin keeping a journal of plants you notice in your neighborhood, noting when they flower, fruit, or change with the seasons.

- Learn to identify: Pick up a regional field guide or download a plant ID app and start learning the names of plants around you.

- Grow something: Whether it’s houseplants, a vegetable garden, or native wildflowers, hands-on growing experience teaches you about plant needs and life cycles.

- Take a class: Look for botany courses at local colleges, botanical gardens, or nature centers.

- Volunteer: Offer your time at a botanical garden, native plant nursery, or conservation organization.

- Join citizen science: Participate in projects like plant phenology monitoring, invasive species mapping, or rare plant surveys.

- Connect with professionals: Join a native plant society or attend botanical talks to meet people already working in the field.

- Visit botany-rich places: Make time to visit botanical gardens, arboretums, and natural areas with diverse plant communities.

- Read broadly: Explore both scientific and popular books about plants to build your knowledge base.

- Stay curious: The best botanists never lose their sense of wonder about the plant world and are always asking “why” and “how” when they observe something new.

- Start small, think big: Even studying the plants in a vacant lot or your backyard can lead to meaningful discoveries and deeper understanding.

- Share what you learn: Teaching others about plants helps solidify your own knowledge and spreads appreciation for the botanical world.

Remember, many professional botanists started simply as people who couldn’t stop noticing and wondering about plants. Your journey into botany can begin today with simple curiosity and attention to the green world around you.

Research References

- Dr. Cassandra Quave https://www.cassandraquave.com/

- Botanical Society of America. (2024). “What Do Botanists Do?” Career resources.

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2023). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

- Missouri Botanical Garden. (2024). “Careers in Botany.” Professional development resources.

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. (2023). “Plant Science Careers and Opportunities.”

- Quave, C. et al. (2022). “Medicinal Plants as a Source of Novel Antibacterial Compounds.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 294, 115387.

- Nadkarni, N. (2023). “Forest Canopy Ecology: A Frontier of Botanical Discovery.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 54, 135-157.

- Mancuso, S. & Viola, A. (2022). The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and Behavior. Atria Books.

- American Institute of Biological Sciences. (2024). “Botanist Career Description.”

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). “Occupational Outlook for Plant Scientists and Conservation Scientists.”

- Center for Native Peoples and the Environment. (2023). “Integrating Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge.”

- American Society of Plant Biologists. (2024). “Plant Science Career Paths and Opportunities.”

- Simard, S. et al. (2021). “Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory.” Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 471-484.

- Gagliano, M. (2023). “Memory and Learning in Plants: A Review.” Plant Signaling & Behavior, 18(1), e2163771.

- Jones, E. K. et al. (2022). “Plant Conservation and Genetic Banking Strategies for Climate Change Adaptation.” Trends in Plant Science, 27(11), 1110-1123.

- Primack, R. B., & Miller-Rushing, A. J. (2022). “Plants and Climate Change: Phenological Responses in a Warming World.” American Journal of Botany, 109(5), 701-715.

- Davis, C. C. et al. (2023). “Digitizing the Green World: Harnessing Digital Plant Collections for Biodiversity Science.” Applications in Plant Sciences, 11(1), e11522.

- Stein, B. A. et al. (2024). “State of Plant Conservation in the United States.” Plant Conservation Alliance and NatureServe Report.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2023). “The State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.”

- National Academy of Sciences. (2022). “Botanical Training for the 21st Century.” Report on Education and Workforce Development.

- Ingram, V. et al. (2023). “Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Sustainable Development: Bridging Traditional and Scientific Applications.” Economic Botany, 77(1), 1-22.

- Wong, W. K. et al. (2023). “Urban Forestry and Green Infrastructure: Plant Solutions for Resilient Cities.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 77, 127722.

- Townsend, P. A. et al. (2023). “Remote Sensing Applications in Plant Ecology and Conservation.” Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 14(2), 520-535.

- Liu, H. et al. (2022). “Plant Responses to Climate Change: Physiological Adaptation Mechanisms.” Journal of Plant Physiology, 270, 153617.

- Ulian, T. et al. (2024). “Global Seed Banking Trends and Challenges for Plant Conservation.” Biological Conservation, 282, 110140.

- Aranda-Rickert, A. et al. (2023). “Medicinal Plants in Pharmaceutical Discovery: Current Approaches and Future Potential.” Journal of Natural Products, 86(3), 723-745.

- Society for Ecological Restoration. (2024). “Botanical Aspects of Ecosystem Restoration: Best Practices Guide.”

- McCouch, S. et al. (2023). “Plant Breeding Innovation for Food Security in a Changing Climate.” Nature Plants, 9(7), 985-999.

- Milla, R. et al. (2022). “Functional Traits in Agriculture: Understanding Crop Adaptations through Plant Evolution.” Trends in Plant Science, 27(4), 387-402.

- Global Plants Initiative. (2023). “Digital Preservation of Botanical Collections: Status and Opportunities.”

- Lee, J. A. et al. (2024). “Phytoremediation Advances: Plant-Based Solutions for Environmental Cleanup.” Environmental Science & Technology, 58(3), 1623-1641.