How to Tell if a Chicken is Laying Eggs

Find Out if Your Chicken is Laying Eggs: Physical Signs and Simple Tests

Look out at your free-ranging flock of chickens and you might find yourself wondering: which of these ladies is still contributing to the egg basket? When you collect eggs from a communal nesting box, it’s not always obvious which hens are productive and which have taken early retirement. Fortunately, a chicken’s body reveals clear signs of her laying status—if you know what to look for.

Let’s explore the scientific methods to identify which hens are still laying and which have stopped, using techniques that connect observable changes to the fascinating biology happening inside your birds.

Understanding the Biology: Why Laying Hens Look Different

Before we check individual hens, it helps to understand what’s happening inside a laying hen’s body. A hen that’s actively laying eggs goes through major body changes – both inside and outside – (what scientists call physiological changes) that affect how she looks and behaves. (If you’d like to learn more about chicken development from egg to adult, check out my post The Life of a Chicken: Chicken Lifecycle)

When a hen is laying, her reproductive system—primarily the ovary (where egg yolks develop) and oviduct (the tube where the egg white and shell form)—is actively producing eggs. This process requires additional calcium, protein, and other nutrients, which affects everything from how her body uses energy to her outward appearance. Her body literally reshapes itself to accommodate egg production!

The average hen takes about 24-26 hours to make a complete egg, from the time the yolk is released (ovulation) to when she lays it. During active laying periods, her body releases egg-making chemicals (hormones, primarily estrogen and progesterone) that surge through her system, causing visible external changes we can observe without any special equipment.

Physical Signs to Tell if a Chicken is Laying Eggs

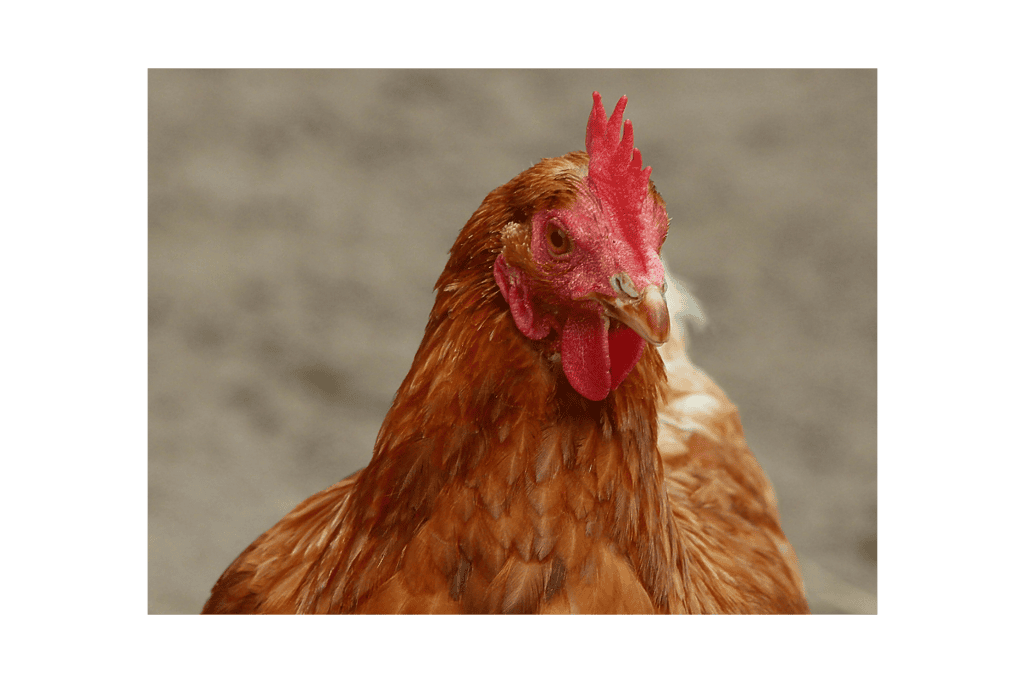

Comb and Wattle Appearance

Look at your hen’s comb (the fleshy red crest on top of her head) and wattles (the dangly bits under her chin). A laying hen typically has:

- Bright red, full, waxy-looking comb and wattles

- Larger, more prominent comb than when not laying

A hen that’s stopped laying usually shows:

- Pale, shrunken, or dull comb and wattles

- Sometimes a dry or scaly appearance

This difference isn’t just cosmetic—it’s directly connected to her body’s egg-making signals. The same body chemicals (reproductive hormones) that trigger egg production also increase blood flow to these areas that are full of blood vessels (highly vascularized areas), making them larger and redder during laying periods.

According to Penn State Extension’s poultry management resources, these visual indicators are among the most reliable ways to assess laying status without handling the birds, making them particularly useful for free-range flocks.

The Vent Check

One of the most reliable indicators is examining a hen’s vent (the external opening where eggs are laid).

A laying hen’s vent:

- Appears moist and oval-shaped

- Is larger and more relaxed

- Looks bleached or pale pink (due to pigment transfer to eggshells)

A non-laying hen’s vent:

- Appears smaller, dryer and puckered

- Has a round rather than oval shape

- Often shows a yellowish color

This color change happens because the yellow coloring that would normally be in a hen’s skin (a pigment called xanthophyll) gets redirected to her egg yolks when she’s laying. After about 2 weeks of laying, her vent area becomes bleached as this coloring is used up from her skin.

Body Structure Changes

A laying hen’s body structure inside actually changes to make room for egg-making:

- Her hip bones (pelvic bones, sometimes called “lay bones”) spread apart to allow eggs to pass

- The space between her breastbone (keel) and hip bones increases

- Her belly (abdomen) feels soft, spacious and pliable

A non-laying hen’s body reverts to a more compact arrangement:

- Pelvic bones move closer together

- The abdominal cavity feels firmer and less expansive

- Overall body feels more solid and less “egg-ready”

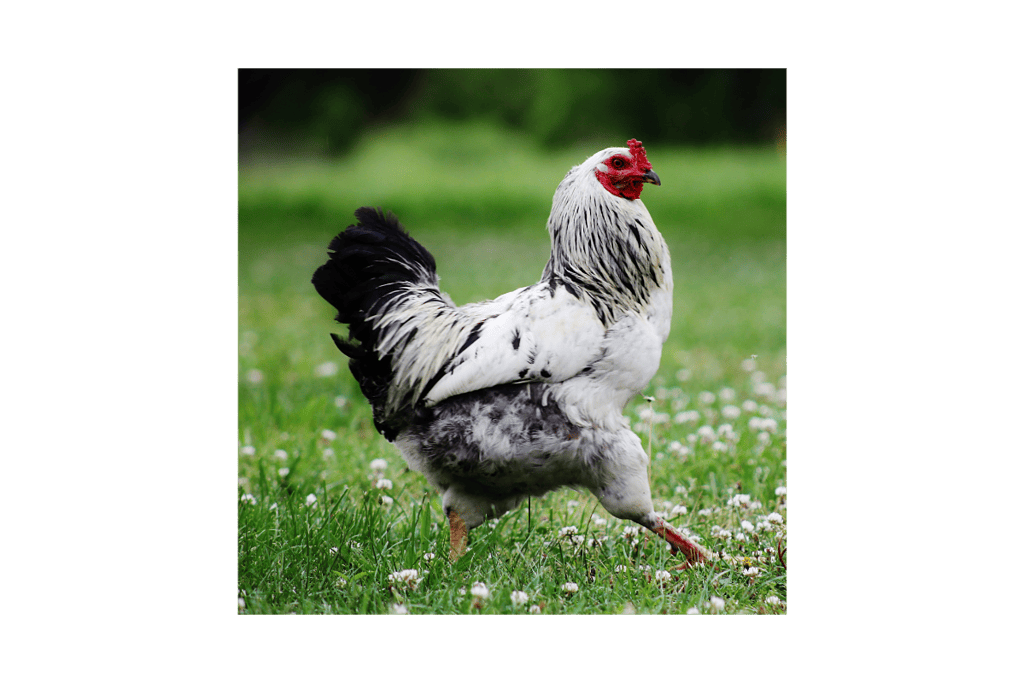

Molting Patterns

Notice your hen’s feather condition. Chickens typically replace all their feathers (molt) once a year, usually in late summer or fall. During this big feather change, egg production typically stops as the hen uses protein to grow new feathers instead of making eggs.

A molting hen:

- Shows patchy feather loss or new pin feathers growing in

- Often appears ragged or scruffy

- Usually suspends egg-laying temporarily

If your hen is actively molting, she’s probably not laying, but this is temporary rather than permanent. Once she completes her molt (which can take 8-12 weeks), she may resume laying.

Hands-On Tests to Tell if a Chicken is Laying Eggs

Now let’s look at some hands-on techniques to determine laying status. These methods work best when your hens are calm and used to being handled. The UC Davis Poultry Health Resources recommend these examination techniques as part of a comprehensive approach to flock management.

The Pelvic Bone Test

This test measures the space between a hen’s pelvic bones, which expand during laying periods.

How to perform the test:

- Hold your hen securely, with her head facing away from you

- Locate the two sharp points of her pelvic bones near her vent

- Measure the space between these bones using your fingers

Interpretation:

- A laying hen typically has enough space to fit 3-4 fingers between her pelvic bones

- A non-laying hen usually has only 1-2 fingers’ width of space

- The more fingers that fit, the more likely she is actively laying

This works because a hen’s body creates space for eggs to pass through her reproductive tract when she’s in laying condition.

The Abdominal Test

This test measures the capacity of a hen’s abdomen, which expands during laying periods to accommodate her active reproductive system.

How to perform the test:

- Hold your hen securely

- Place your fingers on her pelvic bones

- Reach forward with your fingers to find her keel (breastbone)

- Assess the depth, softness and space between these two points

Interpretation:

- A laying hen has a deep, soft, flexible abdomen that can fit 3-4 fingers between pelvic bones and keel

- A non-laying hen has a shallow, firm abdomen with only 1-2 fingers’ width of space

- A laying hen’s abdomen feels more like a water balloon, while a non-layer’s feels more like a firm muscle

This belly space directly relates to the size of her egg-making parts. When a hen stops laying, her egg tube (oviduct) shrinks dramatically from about 25 inches to just a few inches long, taking up much less space in her belly.

Practical Methods to Track Which Chickens Are Laying

Systematic Assessment

For accuracy, examine multiple indicators rather than relying on just one sign:

- Check comb/wattle appearance (bright vs. pale)

- Examine vent (moist/bleached vs. dry/yellow)

- Measure pelvic spacing (wide vs. narrow)

- Feel abdominal capacity (deep/soft vs. shallow/firm)

- Note feather condition (complete vs. molting)

Using this combined approach gives you a much more reliable assessment than any single indicator.

Tracking Individual Hens

For free-ranging flocks where individual monitoring is challenging:

- Consider leg bands with different colors or numbers

- Create a simple chart with physical descriptions

- Check each hen systematically at least once per month

- Record results to track production patterns over time

Early morning is the best time to examine hens, as most laying occurs in the first few hours after dawn. This gives you an opportunity to catch them before they’ve laid for the day when the signs will be most pronounced.

Isolation Testing

If you’re still uncertain about particular hens:

- Set up a separate area to isolate suspicious non-layers (a large dog crate or small pen works well)

- Place the hen in this area overnight with food, water, and nesting material

- Check for eggs each morning for 3-5 days

- A hen who consistently produces no eggs during isolation is likely not laying

This method eliminates the uncertainty of communal nesting boxes where you can’t tell who laid what.

Seasonal and Age Considerations

Remember that egg laying is affected by several natural factors:

- Daylight hours (production often decreases during shorter winter days)

- Age (production typically peaks at 1-2 years, then gradually declines)

- Stress factors (predator pressure, moves, flock changes)

- Heat (extreme temperatures can temporarily halt production)

A young hen who’s not laying in winter may simply be responding to decreased daylight and will resume production as days lengthen. However, a 5-year-old hen showing multiple non-laying indicators might be permanently finished with egg production.

Quick Reference Guide: Laying vs. Non-Laying Hens

| Feature | Laying Hen | Non-Laying Hen |

| Comb/Wattles | Bright red, large, waxy | Pale, shrunken, dull |

| Vent | Moist, oval, bleached/pale | Dry, round, yellow |

| Pelvic spacing | Wide (3-4 fingers) | Narrow (1-2 fingers) |

| Abdomen | Soft, deep, flexible | Firm, shallow, tight |

| Behavior | Visits nesting boxes | Rarely enters nesting boxes |

| Feathers | Complete (unless molting) | May be in molt or complete |

Practical Tips

- Examine hens in the morning before they lay

- Handle birds gently to minimize stress

- Practice on known layers first to calibrate your observations

- Re-check birds after seasonal changes

- Remember that most hens decrease or stop laying in winter unless supplemental light is provided

Conclusion: Becoming an Expert on How to Tell if a Chicken is Laying Eggs

Understanding the biological changes in a hen’s body gives us valuable clues about her laying status. By observing physical characteristics and using simple hands-on tests, you can identify which of your free-ranging hens are productive and which have stopped laying.

Whether you’re making decisions about flock management or simply satisfying your curiosity about who’s contributing to the egg basket, these science-based techniques connect you more deeply to the fascinating biology of your backyard chickens.

To help you put these techniques into practice, I’ve created a free printable Chicken Egg-Laying Assessment Chart that you can download and use with your own flock. This chart makes it easy to track each hen’s physical indicators and production patterns throughout the year. Simply click the link, print it out, and start observing your chickens with a more scientific eye!

Remember that egg production naturally declines as hens age, particularly after their second year. A non-laying older hen still contributes to your flock through pest control, compost creation, and often by maintaining social order. These retirement benefits are worth considering alongside egg production when making decisions about your flock’s composition.

Next time you look at your chickens, you’ll see more than just beautiful birds – you’ll recognize the visible signs of their internal reproductive status, connecting their outward appearance to the remarkable biology happening inside.